SALEM, MY HOME TOWN, is a quiet place, and not many ships call at the port here, though in the last century, before, the war with Britain, the port was often busy. Now the ships go down the coast to the great sea-ports of Boston or New York, and grass grows in the streets around the old port buildings in Salem.

For a few years, when I was a young man, I worked in the port offices of Salem. Most of the time, there was very little work to do, and one day in 1849 I was looking through an old wooden box in one of the dusty, unused rooms of the building. It was full of papers about long-forgotten ships, but then something red caught my eye. I took it out and saw that it was a piece of red material, in the shape of a letter about ten centimetres long. It was the capital letter A. It was a wonderful piece of needlework, with patterns of gold thread around the letter, but the material was now worn thin with age.

It was a strange thing to find. What could it mean? Was it once part of some fashionable lady’s dress long years ago? Perhaps a mark to show that the wearer was a famous person, or someone of good family or great importance?

I held it in my hands, wondering, and it seemed to me that the scarlet letter had some deep meaning, which I could not understand. Then I held the letter to my chest and – you must not doubt my words – experienced a strange feeling of burning heat. Suddenly the letter seemed to be not red material, but red-hot metal. I trembled, and let the letter fall upon the floor.

Then I saw that there was an old packet of papers next to its place in the box. I opened the packet carefully and began to read. There were several papers, explaining the history of the scarlet letter, and containing many details of the life and experiences of a woman called Hester Prynne. She had died long ago, sometime in the 1690s, but many people in the state of Massachusetts at that time had known her name and story.

And it is Hester Prynne’s story that I tell you now. It is a story of the early years of Boston, soon after the City Fathers had built with their own hands the first wooden buildings – the houses, the churches … and the prison.

Hester Prynne’s shame

On that June morning, in the middle years of the seventeenth century, the prison in Boston was still a new building. But it already looked old, and was a dark, ugly place, surrounded by rough grass. The only thing of beauty was a wild rose growing by the door, and its bright, sweet-smelling flowers seemed to smile kindly at the poor prisoners who went into that place, and at those who came out to their death.

A crowd of people waited in Prison Lane. The men all had beards, and wore sad-coloured clothes and tall grey hats. There were women, too, in the crowd, and all eyes watched the heavy wooden door of the prison. There was no mercy in the faces, and the women seemed to take a special interest in what was going to happen. They were country women, and the bright morning sun shone down on strong shoulders and wide skirts, and on round, red faces. Many of them had been born in England, and had crossed the sea twenty years before, with the first families who came to build the town of Boston in New England. They brought the customs and religion of old England with them – and also the loud voices and strong opinions of Englishwomen of those times.

‘It would be better,’ said one hard-faced woman of fifty, ‘if we good, sensible, church-going women could judge this Hester Prynne. And would we give her the same light punishment that the magistrates give her? No!’

‘People say,’ said another woman, ‘that Mr Dimmesdale, her priest, is deeply saddened by the shame that this woman has brought on his church.’

‘The magistrates are too merciful,’ said a third woman. ‘They should burn the letter into her forehead with hot metal, not put it on the front of her dress!’

‘She ought to die!’ cried another woman. ‘She has brought shame on all of us! Ah- here she comes!’

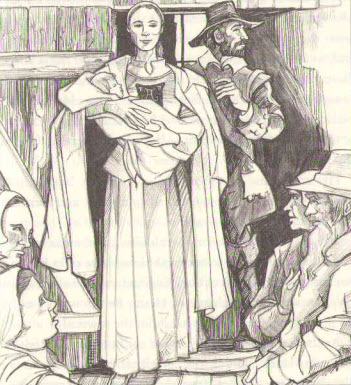

The door of the prison opened and, like a black shadow coming out into sunshine, the prison officer appeared. He put his right hand on the shoulder of a woman and pulled her forward, but she pushed him away and stepped out into the open air. There was a child in her arms – a baby of three months – which shut its eyes and turned its head away from the bright sun.

The woman’s face was suddenly pink under the stares of the crowd, but she smiled proudly and looked round at her neighbours and the people of her town. On the bosom of her dress, in fine red cloth and surrounded with fantastic patterns of gold thread, was the letter A.

The young woman was tall and perfectly shaped. She had long dark hair which shone in the sunlight, and a beautiful face with deep black eyes. She walked like a lady, and those who had expected her to appear sad and ashamed were surprised how her beauty shone out through her misfortune.

But the thing that everyone stared at was the Scarlet Letter, sewn so fantastically on to her dress.

‘She is clever with her needle,’ said one of the women. ‘But what a way to show it! She is meant to wear that letter as a punishment, not as something to be proud of!’

The officer stepped forward and people moved back to allow the woman to walk through the crowd. It was not far from the prison to the market-place, where, at the western end, in front of Boston’s earliest church, stood the scaffold. Here, criminals met their death before the eyes of the townspeople, but the scaffold platform was also used as a place of shame, where those who had done wrong in the eyes of God were made to stand and show their shameful faces to the world.

Hester Prynne accepted her punishment bravely. She walked up the wooden steps to the platform, and turned to face the stares of the crowd.

A thousand eyes fixed on her, looking at the scarlet letter on her bosom. People today might laugh at a sight like this, but in those early years of New England, religious feeling was very strong, and the shame of Hester Prynne’s sin was felt deeply by young and old throughout the town.

As she stood there, feeling every eye upon her, she felt she wanted to scream and throw herself off the platform, or else go mad at once. Pictures from the ‘past came and went inside her head: pictures of her village in Old England, of her dead parents – her father’s face with his white beard, her mother’s look of worried love. And her own face – a girl’s face in the dark mirror where she had often stared at it. And then the face of a man old in years, a thin, white face, with the serious look of one who spends most of his time studying books. A man whose eyes seemed to see into the human soul when their owner wished it, and whose left shoulder was a little higher than his right. Next came pictures of the tall grey houses and great churches of the city of Amsterdam, where a new life had begun for her with this older man.

And then, suddenly, she was back in the Boston marketplace, standing on the platform of the scaffold.

Could it be true? She held the child so close to her bosom that it cried out. She looked down at the scarlet letter, touched it with her finger to be sure that the child and the shame were real. Yes – these things were real – everything else had disappeared.

After a time the woman noticed two figures on the edge of the crowd. An Indian was standing there, and by his side was a white man, small and intelligent-looking, and wearing clothes that showed he had been travelling in wild places. And although he had arranged his clothes to hide it, it was clear to Hester Prynne that one of the man’s shoulders was higher than the other.

Again, she pulled the child to her bosom so violently that it cried out in pain. But the mother did not seem to hear it.

The man on the edge of the crowd had been looking closely at Hester Prynne for some time before she saw him. At first, his face had become dark and angry- but only for a moment, then it was calm again. Soon he saw Hester staring, and knew that she recognized him.

‘Excuse me,’ he said to a man near him. ‘Who is this woman, and why is she standing there in public shame?’

‘You must be a stranger here, friend,’ said the man, looking at the questioner and his Indian companion, ‘or you would know about the evil Mistress Prynne. She has brought great shame on Mr Dimmesdale’s church.’

‘It is true,’ said the stranger. ‘I am new here. I have had many accidents on land and at sea, and I’ve been a prisoner of the wild men in the south. This Indian has helped me get free. Please tell me what brought this Hester Prynne to the scaffold.’

‘She was the wife of an Englishman who lived in Amsterdam,’ said the townsman. ‘He decided to come to Massachusetts, and sent his wife ahead of him as he had business matters to bring to an end before he could leave. During the two years that the woman has lived here in Boston, there has been no news of Master Prynne; and his young wife, you see … ‘

‘Ah! I understand,’ said the stranger, with a cold smile. ‘And who is the father of the child she is holding?’

‘That remains a mystery,’ said the other man. ‘Hester Prynne refuses to speak his name.’

‘Her husband should come and find the man,’ said the stranger, with another smile.

‘Yes, indeed he should if he is still alive,’ replied the townsman. ‘Our magistrates, you see, decided to be merciful. She is obviously guilty of adultery, and the usual punishment for adultery is death. But Mistress Prynne is young and goodlooking, and her husband is probably at the bottom of the sea. So, in their mercy, the magistrates have ordered her to stand on the scaffold for three hours, and to wear the scarlet “A” for adultery for the rest of her life.’

‘A sensible punishment,’ said the stranger. ‘It will warn others against this sin. However, it is wrong that the father of her child, who has also sinned, is not standing by her side on the scaffold. But he will be known! He will be known!’

The stranger thanked the townsman, whispered a few words to his Indian companion, and then they both moved away through the crowd.

During this conversation, Hester Prynne had been watching the stranger – and was glad to have the staring crowd between herself and him. It was better to stand like this, than to have to meet him alone, and she feared the moment of that meeting greatly. Lost in these thoughts, she did not at first hear the voice behind her.

‘Listen to me, Hester Prynne!’ the voice said again.

It was the voice of the famous John Wilson, the oldest priest in Boston, and a kind man. He stood with the other priests and officers of the town on a balcony outside the meeting-house, which was close behind the scaffold.

‘I have asked my young friend’ – Mr Wilson put a hand on the shoulder of the pale young priest beside him – ‘to ask you once again for the name of the man who brought this terrible shame upon you. Mr Dimmesdale has been your priest, and is the best man to do it. Speak to the woman, Mr Dimmesdale. It is important to her soul, and to you, who cares about her soul. Persuade her to tell the truth!’

The young priest had large, sad brown eyes, and lips that trembled as he spoke. He seemed shy and sensitive, and his face had a fearful, half-frightened look. But when he spoke, his simple words and sweet voice went straight to people’s hearts and often brought tears to their eyes.

He stepped forward on the balcony and looked down at the woman below him.

‘Hester Prynne,’ he said. ‘If you think it will bring peace to your soul, and will bring you closer to the path to heaven, speak out the name of the man! Do not be silent because you feel sorry for him. Believe me, Hester, although he may have to step down from a high place and stand beside you on the platform of shame, it is better to do that than to hide a guilty heart through his life. Heaven has allowed you public shame, and the chance to win an open battle with the evil inside you and the sadness outside. Do you refuse to give him that same chance – which he may be too afraid to take himself?’

Hester shook her head, her face now as pale as the young priest’s.

‘I will not speak his name,’ she said. ‘My child must find a father in heaven. She will never know one on earth!’

Again she was asked, and again she refused. Then the oldest priest spoke to the crowd about all the evil in the world, and about the sin that brought the mark of the scarlet letter. For an hour or more he spoke, but Hester Prynne kept her place alone upon the platform of shame.

When the hours of punishment were over, she was taken back to the prison. And it was whispered by those who stared after her that the scarlet letter threw a terrible, ghostly light into the darkness inside the prison doors.

KeyWords

adultery sex between a married man or woman and someone who is not their wife or husband: Many people in public life have committed adultery. adulterous He had an adulterous relationship with his wife's best friend. lane (ROAD) a narrow road in the countryside or in a town: He drives so fast along those narrow country lanes. I live at the end of Church Lane. New England the northeastern US states of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts New Englander someone from New England magistrate a person who acts as a judge in a law court that deals with crimes that are not serious: He will appear before the magistrates tomorrow. Greenway appeared at Bow Street Magistrates' Court to face seven charges of accepting bribes. bosom the front of a person's chest, especially when thought of as the centre of human feelings: She held him tightly to her bosom. A dark jealousy stirred in his bosom. scaffold a flat raised structure on which criminals are punished by having their heads cut off or by being hung with a rope around the neck until they die mistress (SEXUAL PARTNER) a woman who is having a sexual relationship with a married man: Edward VII and his mistress, Lillie Langtry

VOCABULARY

Direct link to the Game